This essay is an expanded version of a presentation at the 2007 DOCAM Summit, Daniel P. Langlois Foundation for Art, Science, and Technology, Montreal, 26 September 2007.

Curators and conservators have traditionally prided themselves on their contact with the original artifact. While readers of histories rely on their imaginations to reconstruct a culture from texts or illustrations, museum visitors glimpse (and sometimes touch) culture on a pedestal directly in front of them. The Elgin Marbles, the Mona Lisa, the Maori spear have travelled far from their place of creation, but they are "here" for the visitor to the British Museum, the Louvre, or the Metropolitan Museum of Art. A nearby label fixes the artifact's date reassuringly in the past, assuaging visitors that the Maori won't return to claim his spear or the Impressionist to touch up his canvas [1]. The marble carver is long dead; the spear has been separated from its user; the oil paint has dried. People associate culture with museums; indeed, they go to museums to be "cultured." But very little culture happens in a museum. Culture takes place in a paint-spattered garret in Bateau-Lavoir, or along a stream in the Australian bush, or around a fire on the Arctic tundra. In many cases, it is happening there still, renewed annually, weekly, sometimes hourly through re-performance and reinterpretation.

People associate culture with museums; indeed, they go to museums to be "cultured." But very little culture happens in a museum. Culture takes place in a paint-spattered garret in Bateau-Lavoir, or along a stream in the Australian bush, or around a fire on the Arctic tundra. In many cases, it is happening there still, renewed annually, weekly, sometimes hourly through re-performance and reinterpretation.

Of course, this ageless tradition of remix and renewal tends to resist glass vitrines and authoritative wall texts, a fact that makes museum professionals more than a little nervous. Yet the best means of caring for contemporary artifacts, whether aboriginal or digital, may lie far beyond the gallery walls in regenerative contexts and processes that kept local culture alive long before books and archives. Museums exhume culture from back Then, and bring it Here. Live culture, meanwhile, is being remade right Now, out There.

It's hard for many of us sequestered away in museums and archives to understand how cultural memory could persevere without the dedication of a staff of experts in a centralized institution. The proliferation of recorded media in the 20th century only seemed to reinforce the necessity of media specialists and climate-controlled warehouses; who else is going to look after those silver gelatin prints and reels of celluloid?

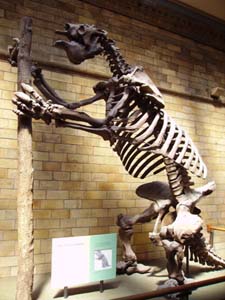

Yet human memory is able to reach further back in time than the artifacts in the deepest storage of today's museums. Sure, the staff of the British Museum can show you Sumerian tablets from 5000 years ago. But Indians of the Brazilian rainforest can recall meeting a paleolithic beast from 50,000 years ago. The giant ground sloth is an impressive creature--20 feet tall, as strong as a dozen gorillas, covered with matted hair covering a bony carapace. Nearly every tribe in the Amazon has a word for this creature, which many call the mapinquary (pronounced ma-ping-wahr-EE), along with stories about human encounters with the animal. Paleontologists have a name for it too: Megatherium, the prehistoric giant sloth. The only problem is, paleontologists believe the Megatherium died out tens of thousands of years ago.

The giant ground sloth is an impressive creature--20 feet tall, as strong as a dozen gorillas, covered with matted hair covering a bony carapace. Nearly every tribe in the Amazon has a word for this creature, which many call the mapinquary (pronounced ma-ping-wahr-EE), along with stories about human encounters with the animal. Paleontologists have a name for it too: Megatherium, the prehistoric giant sloth. The only problem is, paleontologists believe the Megatherium died out tens of thousands of years ago.

Presumed extinct by scientists, these behemoths have nevertheless been kept alive by the folklore of Amazonian Indians through repeated storytelling. What's more, this folklore may tell us things beyond the reach of paleontology, like how the Megatherium smelled: the name mapinquary means "fetid beast." The mapinguary's prehistoric pedigree was corroborated when an Amazon native matter-of-factly told a researcher that he had seen a mapinguary at the natural history museum in Lima. Upon checking, the researcher discovered the museum has a diorama with a model of the Megatherium.

The performative model of preservation dates back even longer than the Megatherium. All life is based on regeneration, as confirmed by a recent study concluding that 98 percent of the atoms in a human body are replaced within a year by other atoms taken in by the body [2]. The indigenous sense of time reflects nature's bottomless cup; as Native elder Diane Gray puts it, the Iroquois think of time not as "past-present-future" but as "now-now-now,"[3] which is perhaps why their sense of responsibility extends seven generations.

Colonial powers have a very different relationship to time. They make museums--often out of artifacts filched from faraway indigenous folks--and the histories they write immobilize culture by fixing it in the past. [4] For historians, time is an instrument for mastering culture.

Curators and conservators also tend to privilege the past over the present. This position of safety reinforces their authority but can diminish the power of the artifact they are trying to represent. Critics of the Sistine Chapel restoration in the 1980s spilled a lot of ink about whether Michelangelo painted in buon fresco or a secco. Look closer at these critics' rhetoric, however, and you'll read their shock at discovering the artist's brazen colors freed from the smoky varnish of time. "Who cares if [chief restorer Gianluigi] Colalucci discovered Michelangelo as a colorist and can explain the Colorist trends of Pontormo and Rossi," wrote one detractor. "His job is to make sure the thing is stuck on there and leave it alone." [5] It's not just works of the distant past whose original luminosity flummoxes art historians and like-minded preservationists. Anyone who has seen 20th-century artist Eva Hesse's fiberglass and resin sculptures in a contemporary museum knows them as brittle constructions of regular, mustard-yellow units such as cylinders or slats. Track down a vintage color photograph from the 1960s, however, and you see that these same handmade shapes once formed colorless, almost immaterial vessels of light. Back when they were first poured, Hesse's painterly training literally shone through her glowing sculptures, as it did in the work of her postMinimal contemporaries Barry Le Va and Sol LeWitt. Unfortunately the light has all but gone out in the lifeless carcasses displayed in most museums. As if the encroach of opacity weren't bad enough, the material these sculptures are built from is gradually disintegrating, to the point where many of them can no longer be installed without turning into a heap of powder on the gallery floor.

It's not just works of the distant past whose original luminosity flummoxes art historians and like-minded preservationists. Anyone who has seen 20th-century artist Eva Hesse's fiberglass and resin sculptures in a contemporary museum knows them as brittle constructions of regular, mustard-yellow units such as cylinders or slats. Track down a vintage color photograph from the 1960s, however, and you see that these same handmade shapes once formed colorless, almost immaterial vessels of light. Back when they were first poured, Hesse's painterly training literally shone through her glowing sculptures, as it did in the work of her postMinimal contemporaries Barry Le Va and Sol LeWitt. Unfortunately the light has all but gone out in the lifeless carcasses displayed in most museums. As if the encroach of opacity weren't bad enough, the material these sculptures are built from is gradually disintegrating, to the point where many of them can no longer be installed without turning into a heap of powder on the gallery floor.

In 2002, San Francisco Museum of Art conservator Michelle Barger, with the participation of the Hesse estate, conducted an experiment to learn more about the late artist's production methods and why they led to the decrepit state of so many of her works. In this experiment, former Hesse assistant Doug Johns re-poured the original polyeurethane moulds used to make the polyester sculpture Sans II. As Barger reports,

I was one of the people in that audience who gasped. In the instant when Johns brought the re-created parts of Sans 2 into the spotlight, I realized how stunning the work must have appeared to Hesse's contemporaries. (Johns said visitors "cried" at the Fishbach opening.) Yet I also was struck by the terror of the present revealed by the audience's reaction--an irrational fear of an object fresh from the artist's hand, undigested by art history, unhistoricized, uncriticized, a glance away from the comforting stack of dog-eared books on the desk and out of the window toward an unfamiliar present.

This schizophrenic stance towards the past is not confined to museum employees, but pervades other "civilized" mechanisms of presentation, from books to archives to documentaries. The last two minutes of Ken Burn's documentary The Civil War features the filmmaker's trademark pan-and-zoom across sepia-toned photographs and vintage footage, set to the voice of historian Shelby Foote echoing a veteran's account of how wondrous it would be to see the dead rise back again to populate an ethereal battlefield in the sky. [7] You have to wonder whether the historian might be a little less dewy-eyed were time's patina stripped off Gettysburg's gore--say, if Foote were suddenly transported from his office surrounded by books onto Cemetary Ridge in 1863 to find himself in the middle of Pickett's charge. It's easy to pretend a fascination with the There and Now when you're sitting in an armchair in the Here and Then.

This schizophrenic stance towards the past is not confined to museum employees, but pervades other "civilized" mechanisms of presentation, from books to archives to documentaries. The last two minutes of Ken Burn's documentary The Civil War features the filmmaker's trademark pan-and-zoom across sepia-toned photographs and vintage footage, set to the voice of historian Shelby Foote echoing a veteran's account of how wondrous it would be to see the dead rise back again to populate an ethereal battlefield in the sky. [7] You have to wonder whether the historian might be a little less dewy-eyed were time's patina stripped off Gettysburg's gore--say, if Foote were suddenly transported from his office surrounded by books onto Cemetary Ridge in 1863 to find himself in the middle of Pickett's charge. It's easy to pretend a fascination with the There and Now when you're sitting in an armchair in the Here and Then.ABOVE: Doug Johns preparing Sans II mock-up, SFMOMA 2002; Sans II mock-up installed next to original work. Both © The Estate of Eva Hesse. Hauser & Wirth Zürich London.

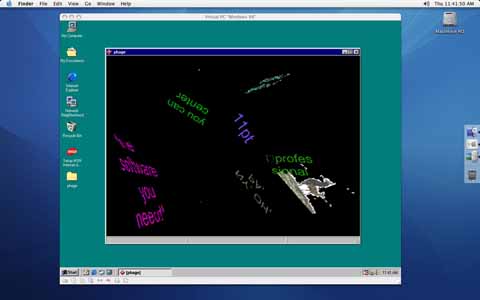

It's not just grapeshot and musket fire that worries historians about the There and Now. Fresh culture, whether pugnacious or painterly, is also raw, sensory, and hard to control. In my days as a museum underling, curators interested in a new artist would tell me not to gather slides, but only what had been written about the artist. For their part, the art professionals on the SFMOMA panel bent over backwards to apologize for the mockup, assuring the audience that it was meant in no way to substitute for the "genuine" sculpture. What makes this fear of the fresh especially dangerous is that re-creation "out there" is the basis for the only preservation solution for digital art that has proven to have any breadth and depth: emulation. By writing emulators--computer programs that simulate old operating systems on newer computers--the dispersed world of gaming enthusiasts has resurrected hundreds of obsolete videogames from the 1980s to the present. The 21st century may never know the astounding luminescence of Hesse's sculptures, but the future of Mario and Zelda is assured.

What makes this fear of the fresh especially dangerous is that re-creation "out there" is the basis for the only preservation solution for digital art that has proven to have any breadth and depth: emulation. By writing emulators--computer programs that simulate old operating systems on newer computers--the dispersed world of gaming enthusiasts has resurrected hundreds of obsolete videogames from the 1980s to the present. The 21st century may never know the astounding luminescence of Hesse's sculptures, but the future of Mario and Zelda is assured.

If the custodians of culture want to amend those priorities, they need to alter their own. Conservation labs and climate-controlled vaults are useful, but they are no substitute for the artists' studios, Usenet groups, and remote villages where culture is birthed and resurrected by its indigenous producers. Conservators need to review strategies such as emulation, migration, and reinterpretation with artists and their assistants well before they are six feet under. Curators need to think of an exhibition hall less as a destination for finished artworks and more as a way station, where works are upgraded and displayed before being routed to their next venue. And museums need to allocate less of their budgets to renting storage space and more to funding the process of creating and re-creating art. [8]

It's time that preservationists focused less on safeguarding the Here and Then, and more on the There and Now.

ABOVE: Mary Flanagan's [phage] running in Windows 98 emulated within Mac OS X.

1. Pierre Bonnard is supposed to have tried to retouch one of his exhibited paintings at the Palais du Luxembourg before being discovered by a guard.

2. "Atomic Tune-Up: How the Body Rejuvenates Itself," Weekend All Things Considered, National Public Radio, July 14, 2007, transcript at http://nl.newsbank.com/nl-search/we/Archives?p_product=NR&d_origin=transcripts&z=NR&p_theme=nr&p_action=search&p_maxdocs=200&p_topdoc=1&p_text_direct-0=11A6682400161070&p_field_direct-0=document_id&p_perpage=10&p_sort=YMD_date:D&s_trackval=GooglePM, accessed on July 24, 2008.

3. Diane Gray, in discussion at Connected Knowledge 2007, Banff New Media Institute, July 28, 2007.

4. In contrast to the European tendency to fix artifacts in the past, the Swahili believe it is impossible to display historical objects. "Swahili culture is divided into Sasa (roughly, the present moment plus or minus a year) and Zamani (everything before that, with some overlap). As events scroll past living memory, they turn from Sasa to Zamani, accruing in the process historical significance as well as story and myth. A Swahili might therefore find absurd the notion of displaying an artifact in a museum: curators might try to display a relic to evoke an aspect of Zamani, but any object in plain view is experienced as Sasa. Even relatively recent works suffer from this paradox, since anything deemed worthy of preservation will have some sort of mythos built around it, no matter how short." For the Swahili, in other words, any object in the Here is always of the Now. John Bell, personal email to the author, July 24, 2008. For more on Sasa and Zamani see John S. Mbiti, African Religions and Philosophy, (Oxford; Portsmouth, N.H.: Heinemann, 1990). Benjamin Whorf makes a similar claim for the Hopi sense of time; see Language, Thought, and Reality: Selected Writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf, John B. Carroll, ed. (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1964).

5. Peter Layne Arguimbau, "Michelangelo's Cleaned off Sistine Chapel," posted on October 5, 2006 at http://www.arguimbau.net/article.php?sid=8, accessed on July 24, 2008.

6. Michelle Barger, "Thoughts on Replication and the Work of Eva Hesse," Tate Papers, issue 8 (Autumn 2007), at http://www.tate.org.uk/research/tateresearch/tatepapers/07autumn/barger.htm, accessed on July 24, 2008.

7. "Who knows, but it may be given to us after this life to meet again in the old quarters....again the old flags, ragged and torn, snapping in the wind, may face each other and flutter, pursuing and pursued while the cries of victory fill a summer day. And after the battle, then the slain and wounded will arise and all will meet together under the two flags all sound and well. And there will be talking and laughter and cheers. And all will say, did it not seem real. Was it not as in the old days." Sergeant Barry Benson, South Carolina veteran of the Army of Northern Virginia, quoted by Shelby Foote in Ken Burns, The Civil War, Public Broadcasting System, 1990. Transcribed by the author.

8. As one example, the Guggenheim earmarked about 15 percent of the acquisition budget for its 2002 Internet art commissions for an endowment meant to fund future re-creations of the works.